Salesforce Sustainability: Designing Behavioral Nudges for Workplace Sustainability

Behavioral Design | Sustainability

I designed a system that helped Salesforce employees reduce their digital carbon footprint without disrupting their workflow by making invisible energy costs visible at the moment of decision.

The Core Challenge: Salesforce employees wanted to practice sustainability at work, but didn't know how their daily digital actions (video calls, file storage, dashboard refreshes) contributed to energy consumption. Awareness existed, but behavior didn't change because impact felt abstract and actions felt effortful.

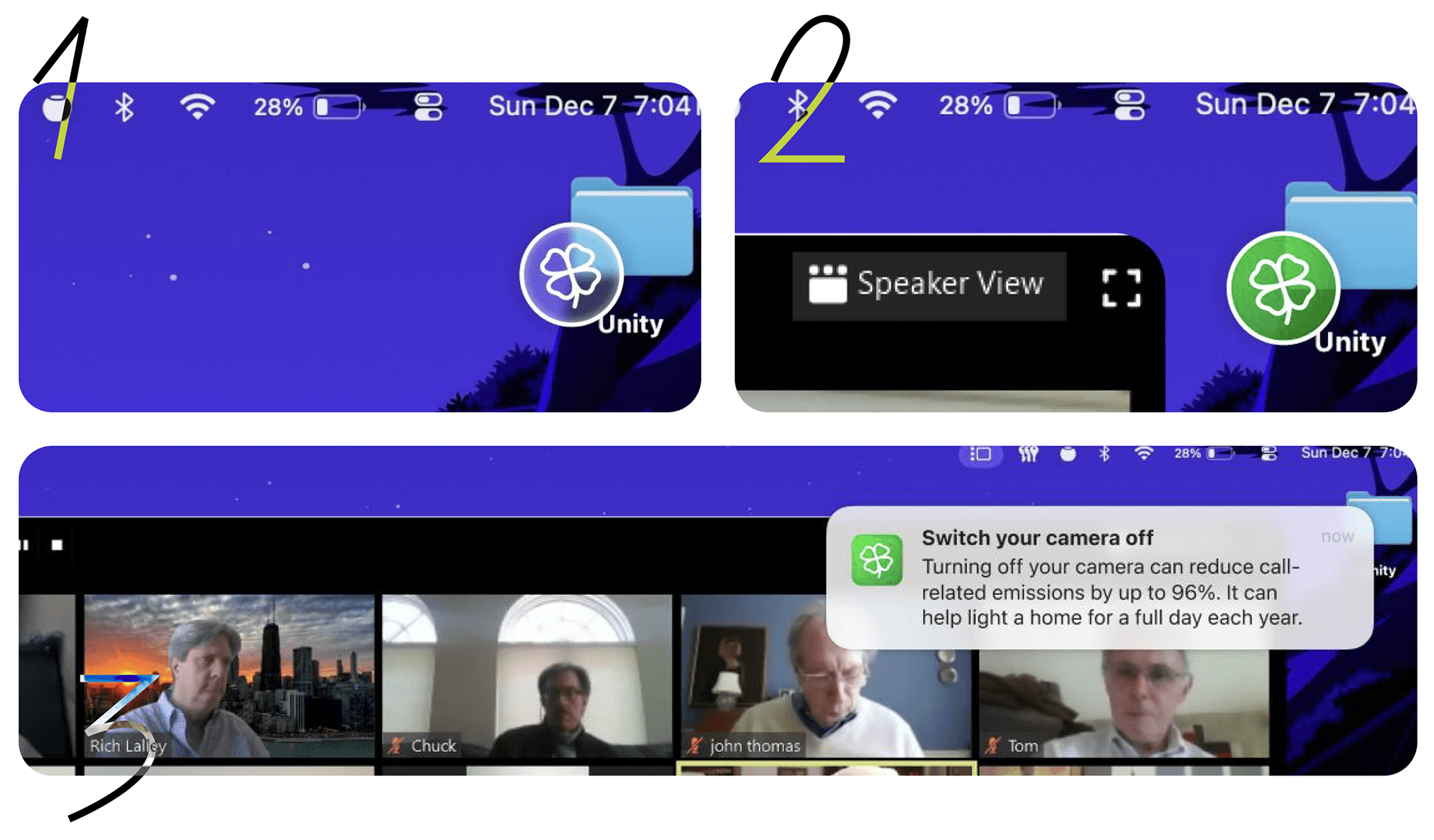

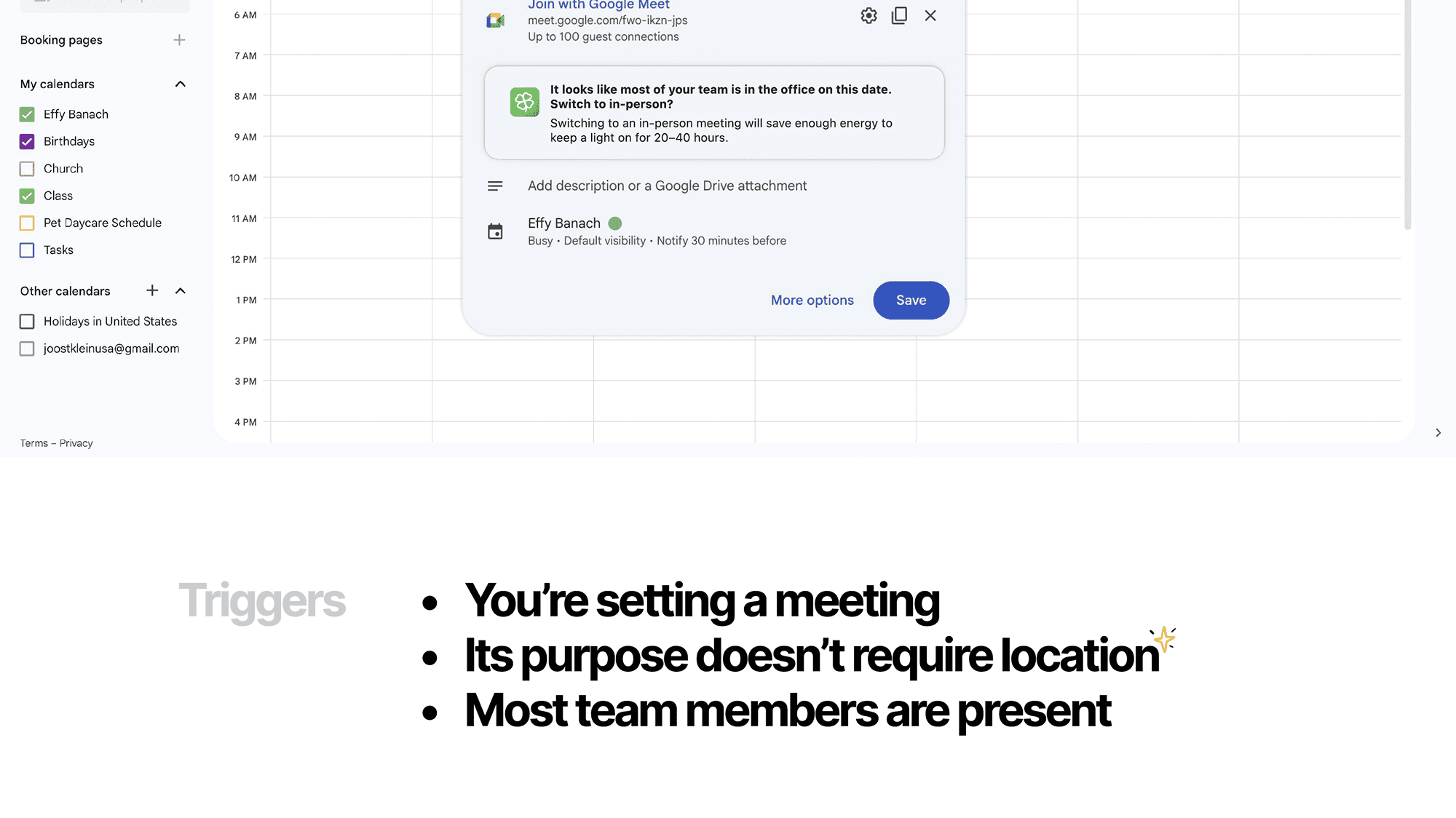

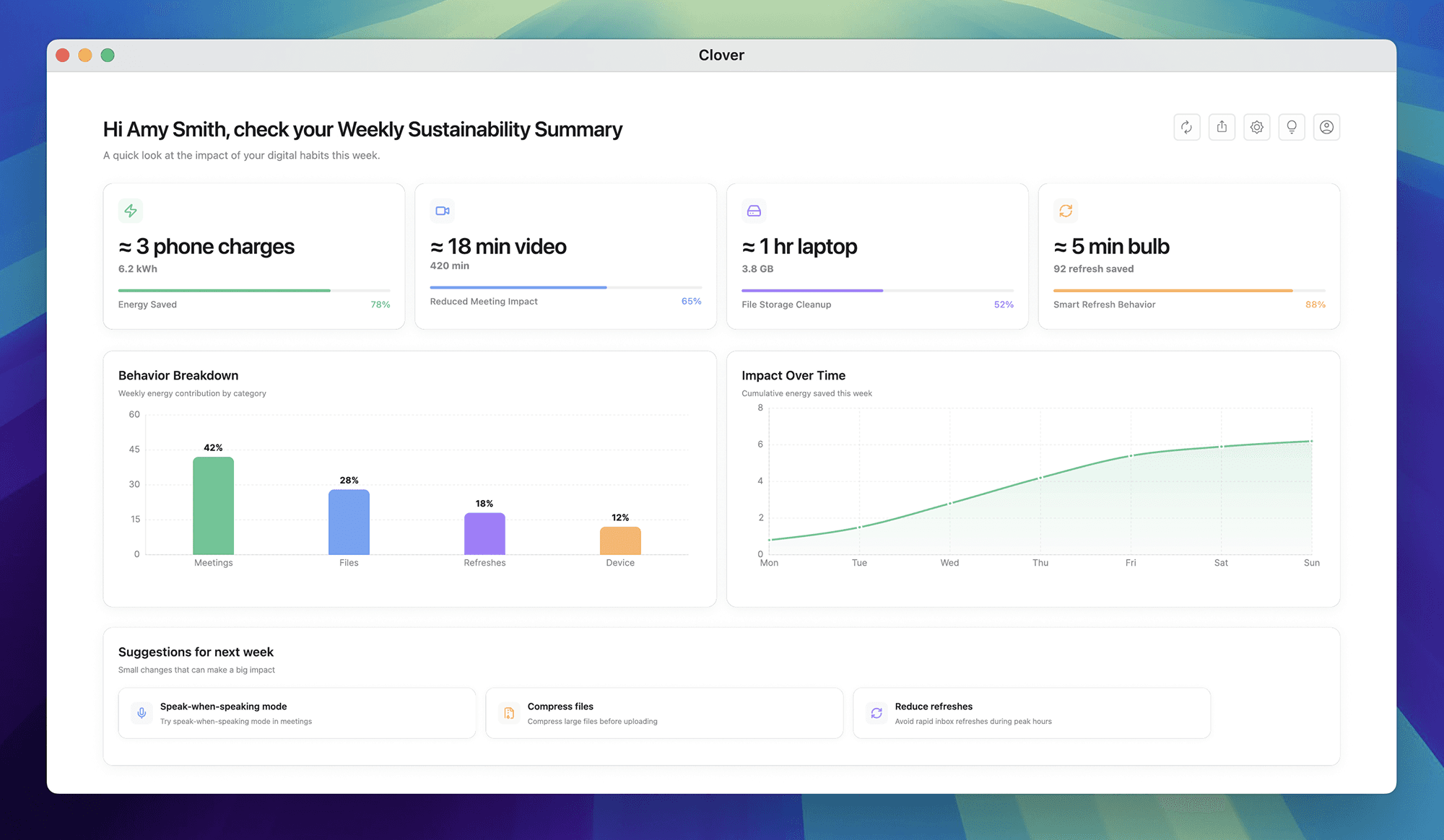

My Approach: Instead of building another sustainability dashboard employees would ignore, my team and I designed Clover, an ambient widget that surfaces contextual nudges only when a sustainable alternative exists and the cost of change is low. Green means "you can act now." Blue shows weekly impact. The system stays silent until it matters.

The Impact: User testing showed employees found Clover "immediately understandable" and "lightweight enough to engage with during busy periods" unlike typical enterprise features that require explanation. But more importantly, this project taught me that behavior change isn't about motivation. It's about reducing friction at the exact moment someone can make a different choice.

The Real Problem Wasn't Awareness, It Was Action

Salesforce had already invested heavily in corporate sustainability initiatives: carbon offset programs, renewable energy partnerships, sustainability training. Employees knew climate change mattered. They wanted to help. But nothing was changing.

When we interviewed employees, we heard the same pattern:

"I care about sustainability, but I don't know what I can actually do at work." "I carpool when I can, I bring my own coffee mug, but at my desk? I have no idea." "Does turning off my camera in meetings really make a difference? It feels like a drop in the ocean."

The insight that reframed everything:

The gap wasn't between values and awareness. It was between awareness and action. People understood sustainability mattered. They just didn't know which actions mattered, when to take them, or whether their effort would create meaningful impact. This is where most corporate sustainability programs fail. They treat behavior change as an education problem ("if people just knew more...") when it's actually a friction problem ("people know, but acting on it feels too hard or too vague").

What We Discovered About Digital Carbon Footprint:

Our research focused on something most people don't think about: the energy consumption of everyday digital work.

We found that practices like:

Keeping cameras on during long meetings

Maintaining multiple live dashboards that auto-refresh

Storing redundant or outdated files in cloud storage

...all consume energy continuously, often without employees being aware of it.

The scale surprised us. Studies show that a single one-hour video call with camera on can consume as much energy as charging your phone for a full year. Multiply that by thousands of employees in daily meetings, and the impact compounds fast.

But here's the problem:

These energy costs are invisible. Unlike turning off a light switch (immediate, visible feedback), digital energy consumption happens in data centers employees never see. The cause-effect relationship is completely abstract.

The direction this pushed us toward:

We needed to make digital energy consumption contextual, visible, and actionable at the moment of decision. Not through abstract metrics like "kilowatt hours" (meaningless to most people), but through relatable, human-scale impact framing.

Instead of "You saved 2.4 kWh this week," we'd say: "Your choices this week saved enough energy to power 2 homes for a month."

The Framework: The Ambient Nudge System

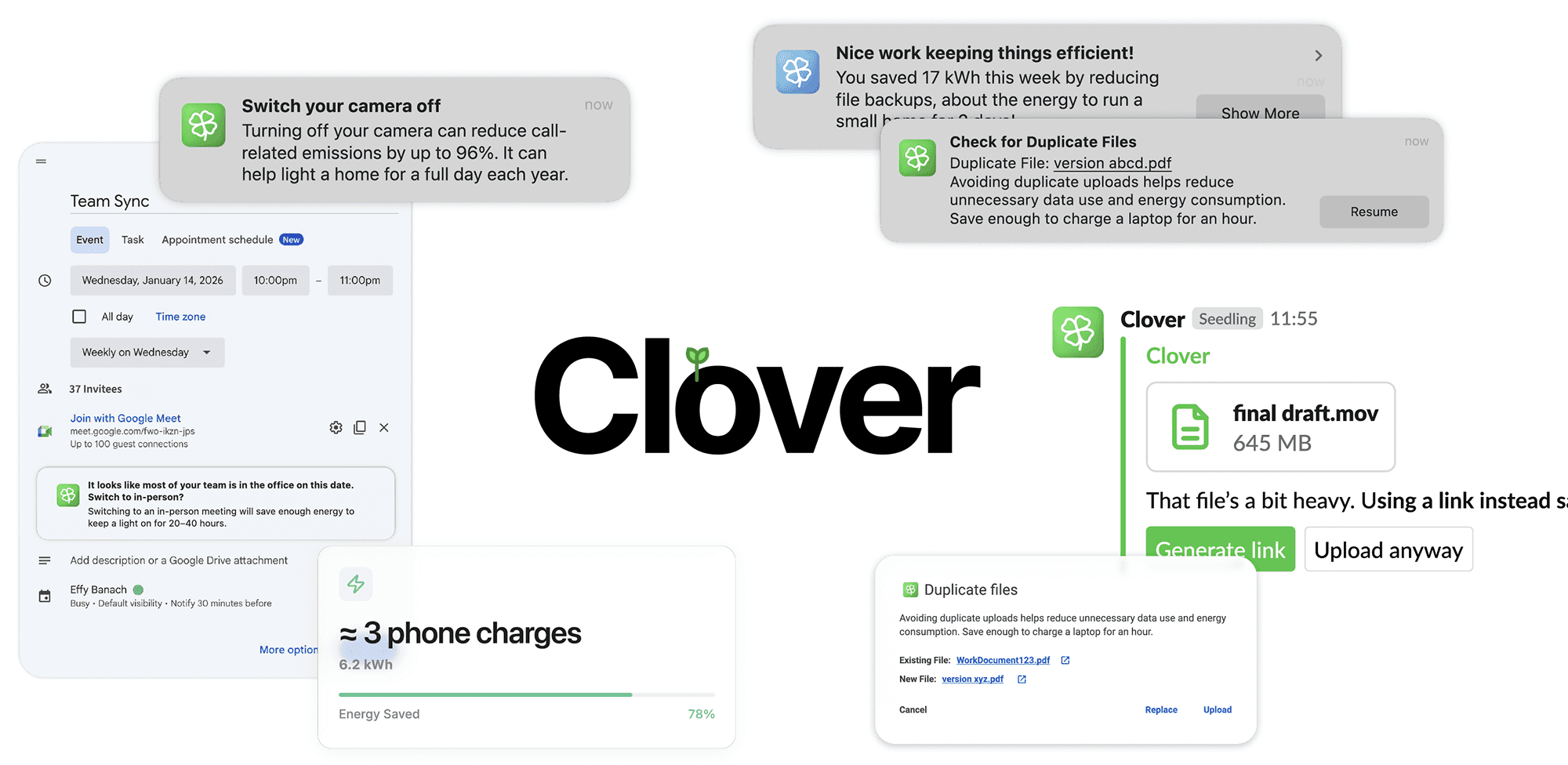

We designed Clover around a principle I call "silent until significant". The system remains invisible until three conditions are met:

A sustainable alternative exists (not just awareness, but a real action the user can take)

The user is at a decision point (about to start a meeting, upload a file, schedule something)

The behavioral cost of change is low (it won't disrupt their work or require significant effort)

This framework came directly from behavioral science research, particularly BJ Fogg's Behavior Model: Behavior = Motivation × Ability × Prompt. Most sustainability tools focus on motivation (guilt, inspiration, peer pressure). Wr focused on ability (making the sustainable choice the easier choice) and timing (prompting at the exact moment of decision).

The Design Pattern System

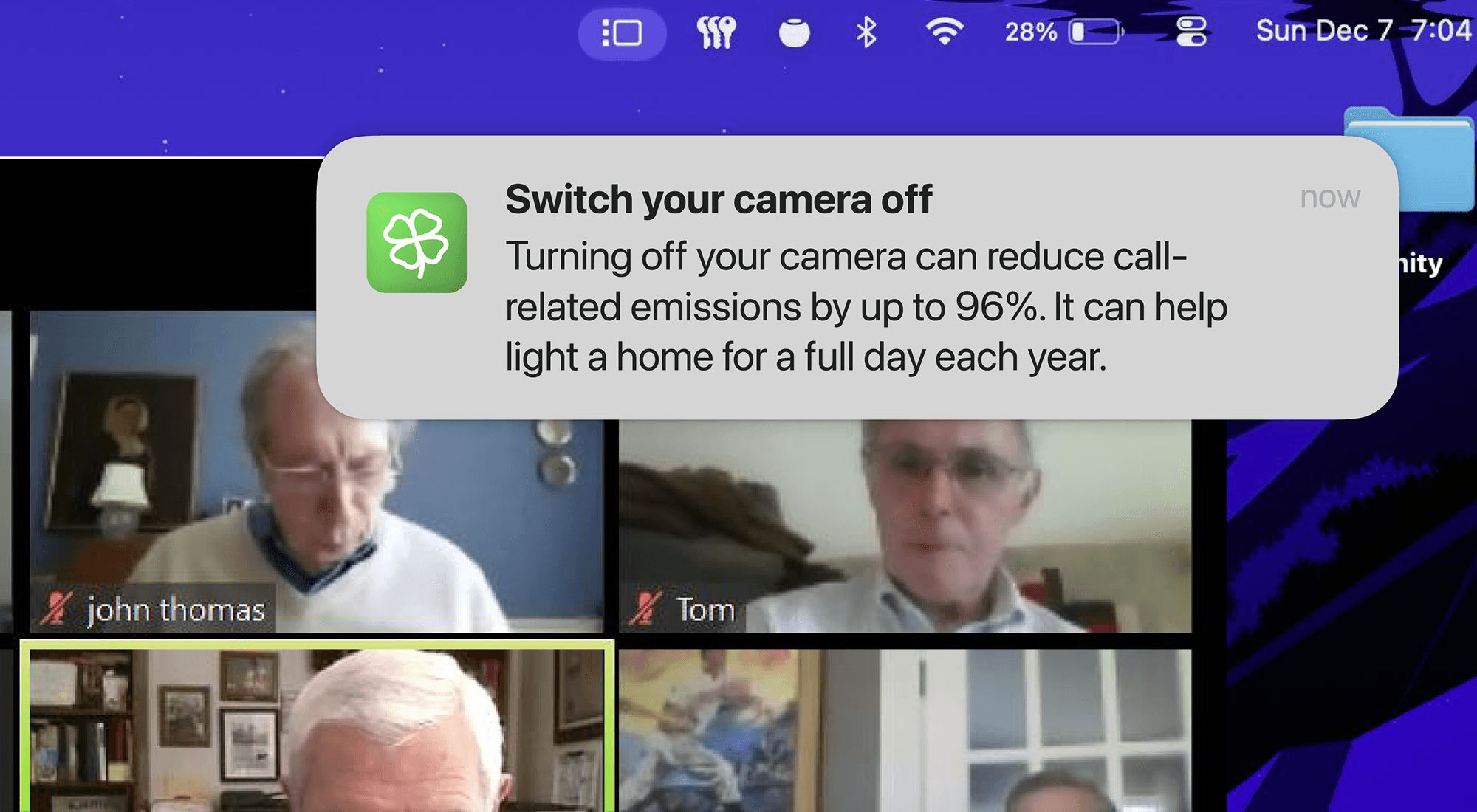

Passive Nudge: Clover lives as a translucent widget in the corner of the screen. It's visible but not attention-demanding, you can ignore it if you're focused, but it's noticeable enough that eventually you'll wonder "why is it green today?"

Active Nudge: When Clover detects a trigger (e.g., you're about to upload large, duplicate files to cloud storage), the icon turns green. This is the prompt, not a pop-up, not a modal, just a state change that signals "there's something you can act on."

Impact Framing: When you click the green icon, you see the specific action you can take AND the impact it will create. Not "delete duplicate files" (feels like work), but "Deleting these duplicates would save enough energy to power 3 homes for a day" (feels like contribution).

Reinforcement: The blue state shows your cumulative weekly impact. This isn't gamification, it's social proof that your small actions are adding up to something meaningful.

Automation Offer: For repeated behaviors (like always turning off camera in large meetings), Clover offers to automate the choice. This reduces future friction even further.

The Decisions That Made This Work (And What I Argued Against)

Decision 1: Ambient Widget vs. Dashboard

Should Clover be a separate dashboard employees open when they want to check their impact, or an always-visible ambient element in their workflow?

What stakeholders wanted: A sustainability dashboard. It felt more "feature-complete," easier to explain in presentations, and aligned with how other enterprise tools work.

Why I argued against it: Dashboards require intentional engagement. You have to remember they exist, decide to open them, interpret the data, and then translate that into action later. Every step is friction.

Our user research was clear: "If it's one more thing I have to open and check, I won't do it. I'm already drowning in tools."

What we chose: An ambient widget that lives persistently in the workflow. It doesn't require a decision to engage. It's just there, and occasionally it turns green. A dashboard was designed as an add-on capability to oversee progress over time.

But we optimized for action over analysis. The goal wasn't to make people sustainability data experts, it was to help them take one small action today, and another tomorrow, until it became habit.

Decision 2: When to Surface Nudges

The biggest design risk: Nudge fatigue.

If Clover interrupts too often, employees will ignore it (or worse, disable it). If it surfaces at the wrong moments like mid-presentation, during a critical debugging session, it becomes annoying rather than helpful.

What we designed:

Clover only surfaces nudges when the user is at a natural decision point (about to start a call, about to upload files, scheduling a meeting for next week)

It never interrupts mid-task (no pop-ups during active work)

The green state is persistent, not time-limited. If you're busy, you can engage with it later. It's a signal, not a deadline.

What remains unresolved: We proposed explicit governance rules for future work:

Maximum 3 nudges per day

No nudges during blocked "focus time" on calendar

Users can disable specific nudge categories (e.g., "I need dashboards to auto-refresh for my job, stop suggesting I turn that off")

Why I flagged this as critical:

Attention is the scarcest resource in workplace software. If we abuse it with sustainability nudges, we undermine the entire mission. Better to show 1–2 highly relevant nudges per week than 10 semi-relevant ones per day.

What Worked: Perceived Simplicity and Low Cognitive Load

Participants consistently responded positively to the simplicity of the interaction. One user said:

"Unlike most enterprise features that require explanation, this felt immediately understandable. I didn't have to read a help doc or watch a tutorial, I just got it."

The absence of complex pop-ups, layered modals, or forced workflows was specifically called out. Multiple participants said they were more willing to engage with Clover during busy periods because it appeared work-relevant and lightweight, not like "another corporate initiative I'm supposed to care about."

Tone and Personalization

Users responded strongly to how Clover communicated. Instead of robotic system messages like "You have exceeded recommended storage capacity," Clover said things like:

"You have 3 large files from 2022 that haven't been opened in a year. Archiving them would save enough energy to power a coffee maker for a week."

The tone felt human and conversational, not instructional. Several users explicitly contrasted this with typical system-generated messages they normally ignore.

The personalization angle was critical

When Clover referenced peer behaviors ("40% of your team turned off cameras in meetings this week"), it made the action feel social rather than individual. Sustainability became a shared practice, not a lonely burden.

Visibility Without Disruption

One of the most important validation points: Clover struck a balance between noticeable and non-intrusive.

A user said:

"Even if I ignore it a few times, there will be some day where I go 'oh, what is this, why is it green today?' and I'll click it. It's there when I'm ready for it."

This was exactly the behavior model I designed for. Clover doesn't demand immediate action, it creates ambient curiosity that eventually leads to engagement on the user's terms.

What We Intentionally Left Unresolved (And Why That's Honest Design)

During our final presentation, we deliberately called out challenges and limitations, not as oversights, but as honest acknowledgments of what a V1 solution can and can't solve.

Challenge 1: Data Privacy and Trust

The concern: For Clover to detect opportunities (duplicate files, camera usage in meetings, dashboard refresh rates), it needs access to user data. In enterprise environments, trust and compliance are non-negotiable.

Our proposed approach:

Local-first analysis wherever possible (processing happens on the user's device, not in a central server)

Metadata-only inspection by default (file size, type, timestamps and not file contents)

On-device hashing for duplicate detection (so raw content never leaves the user's machine)

Zero data retention by Clover itself (no logs, no tracking, no surveillance)

What we couldn't fully resolve: Region-specific data protection laws (GDPR, CCPA), role-based data visibility across teams, and IT approval workflows. These require legal and compliance teams to weigh in.

Why I flagged this explicitly: As designers, we could propose a privacy-first technical architecture, but we couldn't guarantee it would pass enterprise security review. Being honest about this boundary shows design maturity. I know where my expertise ends and where other disciplines need to step in.

Challenge 2: The AI Sustainability Paradox

Throughout this project, faculty and peers encouraged us to explore AI-driven directions: "What if Clover used machine learning to predict the best time to surface nudges? What if it personalized suggestions based on individual behavior patterns?"

we deliberately avoided introducing AI into the core system.

Here's why: AI can optimize behavior, but it also consumes significant energy in doing so. Running machine learning models requires compute power, which requires energy, which contributes to the exact problem we're trying to solve.

This is the AI sustainability paradox: the tool designed to reduce carbon footprint might increase it through its own operation.

If we were to explore AI in future versions, we'd need to answer:

What's the energy cost of AI computation vs. the energy saved through behavioral change?

How do we measure net impact?

When is AI active, and how much autonomy does it have?

Can we be transparent about the environmental cost of the AI itself?

Challenge 3: Long-Term Behavior Change

User testing showed Clover was approachable and engaging in the short term. But long-term behavior change is still an open question.

Nudges can initiate awareness, but sustained change depends on culture, reinforcement, and shared norms. One nudge doesn't create habit, repeated nudges plus social proof plus organizational support do.

What This Project Changed About How I Approach Design

When I started this project, I thought I was designing a sustainability tool. By the end, I realized I was actually designing an intervention system, and that reframing changed everything about how I think about my work as a designer.

Throughout this project, I had eye opening conversations with people at Salesforce about the role of AI in sustainability work. Many encouraged us to use AI and ML to personalize nudges and predict optimal intervention moments. We chose not to use AI in V1, because AI systems consume significant energy, creating what I call the AI sustainability paradox:

The tool designed to reduce carbon footprint might increase it through its own operation.

But the most valuable insight came from how Salesforce employees reframed this tension. They pushed me to think beyond the immediate energy cost and consider the compounding effect over time. The question isn't "Is AI sustainable right now?"

The question is:

Are we designing AI systems responsibly for the future they're compounding into?

If an AI system consumes energy today but enables behavioral changes that reduce energy consumption at scale over years, the net impact could be positive.

This is the kind of systems thinking I didn't have before this project. I'm no longer asking "Should we use AI?" I'm asking "Under what conditions does AI create net positive impact, and how do we design accountability into that assumption?"

Final Reflection

This project taught me to think about designing for systems, not just screens.

I learned that impact isn't always measurable in the moment, sometimes you design the foundation for change that takes years to compound.

I learned that honesty about limitations is more valuable than claiming false certainty.

And I learned that the most important design question isn't "What should this look like?" It's "What does this create downstream, and am I designing responsibly for that future?"